Some of you, in rooting around in your camera's manual - may have discovered that you can also change your "shutter speed."

Most camera's are digital these days - but a lot of the terms we use are holdovers from the still fairly recent days of mechanical cameras - so while they don't really function the same way - as the underlying mechanism isn't quite the same - we still talk about "shutter speed," "f-stop," "aperture," and, most bizarrely, "film speed." As some point, some young camera designer with have a "what the heck moment" and come up with some new ideas and terms that utilize the strengths of the digital medium instead of seeking to replicate an old one, but, until then, we have a "legacy language" to use.

So, in the olden days, the shutter was a "curtain" behind the lens that stopped light from getting to the film, and you could control how long it stayed open, and thereby control how much light fell on the film, and consequently, how light or dark the resulting picture was.

In the process of doing this, folks discovered that not just the brightness and darkness of the picture changed, but some other characteristics too. Such as the "depth of field" - which is to say - the amount of the picture that was in focus.

Think for a moment about a picket fence - imagine standing at the very end of a looong picket fence, and then think about looking down it, one picket, two, ten, 30, - and the entire length of it. If you take a picture of it - how much of it will be in sharp focus? Maybe the first 10 feet? Maybe all of it? Maybe you'd like to make a picture that emphasizes how long the fence is, and so if the first 10 feet are sharply focused, and then the rest gets soft and blurry - so the end of the fence is just a white blur - then the picture will make you think of distance and depth - and be more interesting than if the whole thing is sharply focused. And that, of course, is more artistic than we are trying to do here. However, we can still take that understanding of that technique, and use it for our own purposes.

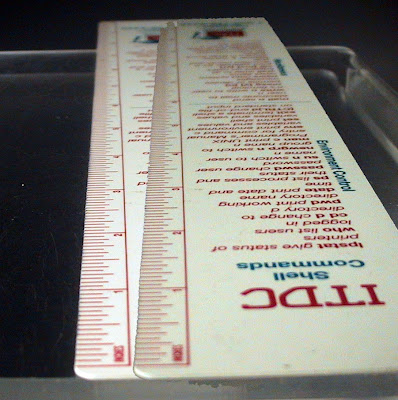

The photo above is actually two separate photos, one overlaid on top of the other. The ruler to the left and behind was shot with the shutter speed manually set to 1/60 - which is short for 1/60th of a second. The ruler on the right and on top was photo'd at 1/250 - 1/250th of a second - which is a much "faster" shutter speed - a shorter length of time. Once upon a time - this literally would be the length of time that the "shutter" would be open, exposing the film to light. Nowadays - it's a digital simulation. But even so, you can see that there has been something rather interesting happen.

Not only is the picture on the left brighter, doh, more light, but more of it is in focus (remember - depth of field?) and look at the distortion that has happened on the image on the right! The camera was in the exact same position for both pictures. (Strapped down to a brick, as a matter of fact.)

So - you can see that if you are photographing a necklace, and you want it to be representative of what you actually have - the slower shutter speed will give you a more accurate, less distorted picture, with more of your object in focus. Try this with your own camera - see what sort of results you get!

Oh, btw - it is generally accepted by photo-wonks that anyone can hold a camera steady long enough to take a picture at 1/60 without the camera moving while the shutter is open and blurring the picture. 1/30 is a little trickier, but can be learned - longer requires a tripod. That's why photo buffs are so keen on tripods. They like slower shutter speeds, and now you see why.

To hold the camera steady - tuck your elbows into your body and hold the camera firmly. Steadying it on something is good too. Take a breath, hold it, and squeeze the shutter button - so you have your hand wrapped around the camera and you are pushing the button, but pushing against something solid, i.e. the other side of your hand. Don't poke, push or, gawd forbid "snap" - the shutter. A nice gentle squeeze - so that your act of taking the picture doesn't cause the camera to move. If the camera moves while the picture is being taken, the entire picture is blurred. If only part of the picture is blurred, then the object moved (i.e. kids, cats, dogs). Of course - it is possible to do both - resulting in one of those pictures you delete.

4 comments:

OMG...thank you so much!!! This will make the world of difference in photos of my jewelry:)

Ditto!! You have done a smashing job on this. Tomorrow I will sit down with my two manuals and start trying out the different things you have covered.

Many thanks on behalf of all of the photography-challenged beaders!! (G)

To say that the depth of field (the amount of the object that is in focus) is affected by the shutter speed is a little misleading.

It's the aperture (or size of the opening) that is really affecting the depth of field. The bigger the opening, the more light gets in, the less of the object is in focus. Yes, the shutter speed is affected, but if someone wants to control depth of field, it's really the aperture they should be adjusting, rather than the shutter speed.

The two work in concert - and if your camera won't let you change the aperture - you really have no choice but to manipulate the shutter speed.

Post a Comment